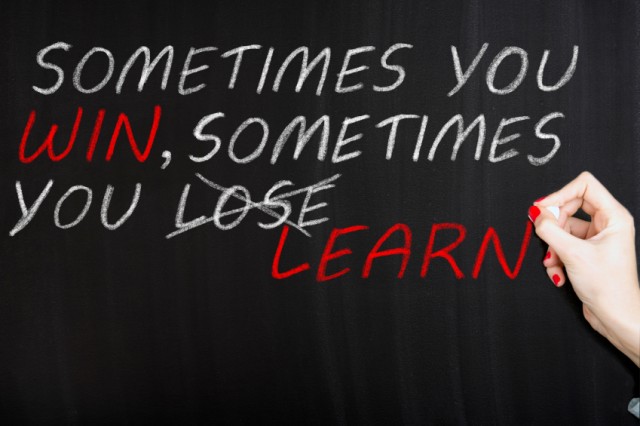

You’ve developed common practices you take for granted.

But, when was the last time you examined whether those “common practices” still represent “best practices”?

Several years ago when my father was in his final days, his bonhomie in full bloom, I sat in the room while the doctors administered a few basic tests to assess his cognition.

“

“What country do you live in,” they asked and Dad answered correctly.

“What city do you live in,” they asked. Dad answered “Grand Rapids,” correct again.

“What state do you live in,” they continued. Dad, ever alert, laughed and responded …

“Discombobulation.”

So, how do we shake things up?

I’m always fascinated by the breadth and depth of professional sports analytics these days.

You only have to watch a few TV sports events to see some of the remarkable statistics and tracking data that’s collected and graphically displayed in real time.

What they teach you … and what directly applies to your organization … is that by thoughtfully considering currently available data, you may discover that what you’re doing every day no longer represents Best Practices.

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I … I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.”

Robert Frost

Sports data provides powerful examples of this phenomenon. It is more visually compelling and demonstrates how easily we can become complacent, completely ignoring the data. In other words, it’s time to take a few calculated risks to see if you can generate some new ideas.

I read recently about Kevin Kelly, a high school football coach in Arkansas, who has developed a few football rules that most of us would find ludicrous, to wit:

- His team hasn’t punted since 2007, when it did so as a sportsmanlike gesture in a very one-sided game.

- They don’t kick field goals.

- They don’t run back punts. They don’t even try to catch them.

- They love onside kicks.

There’s more, but you get the gist.

Much of the basis of his game plan originated with a documentary he saw, supported by the work of David Romer, a Cal economist who published a study conducted covering three NFL seasons.

Mr. Romer’s academic interest emanated from his curiosity about how firms react to competition and whether they truly act to maximize their chances for profitability. He thought football offered an empirical way to test strategic decision-making, since there are myriad details about the situations faced by teams when those decisions are made.

I downloaded his white paper in which he closely examined the fourth down decisions made in the NFL on whether to punt or go for a first down. You’ll find a more current and very detailed analysis, 4th Down Study, from Advanced Football Analytics by Brian Burke.

If you kids played soccer ....

If soccer is your sport, visit Google and look up “penalty kicking in soccer”. You’ll find dozens of studies that conclude that current strategies are inconsistent with the results of those strategies … yet those failing strategies still prevail.

In soccer, goalies are rewarded by standing in the middle of the goal awaiting the kick … anything else would look stupid … and yet, that strategy fails much more than it succeeds. ESPN’s Sports Science series illustrates this data.

Check out these metrics

Football may not be your thing, but with even a cursory understanding of the game, some of the metrics that Kelly and Romer uncovered for each of the four enumerated situations illustrate how our preconceived notions aren’t always supported by the data:

- On the team’s own half of the field, going for it on fourth down is usually better as long as there are less than four yards to go.

- Moreover, within the opponent’s five-yard line, a team is always better off by going for it, yet we rarely see that happen.

- Particularly in high school where the punts don’t go so far, Mr. Kelly has concluded that the risk of fumbling or a penalty outweighs the value of punting.

- According to Mr. Kelly’s figures, the receiving team after a kickoff takes over on its own 33-yard line on average. After a failed onside kick, the team assumes possession on its 48-yard line. Since they typically recover about 25 percent of their onside kicks, he figures you’re giving up 15 yards for a one in four chance to get the ball back, a risk he says he’ll take every time.

Are you always taking the easy road?

For most of us, it’s convenient to take the easy road and make the decisions we believe are expected of us rather than ones that are more unconventional and may be challenged.

In many ways, we’re like some of these football coaches, acting conservatively because, like them, we might get fired for “going for it” and missing, but we’re rarely fired for punting on fourth down.

Maybe that’s the wrong approach in this competitive business environment.

Maybe it’s time to go for it!

Question: What practices are you following that you suspect no longer represent best practices?

Got Comments?

Please leave your comments below or email me at lary@exkalibur.com.